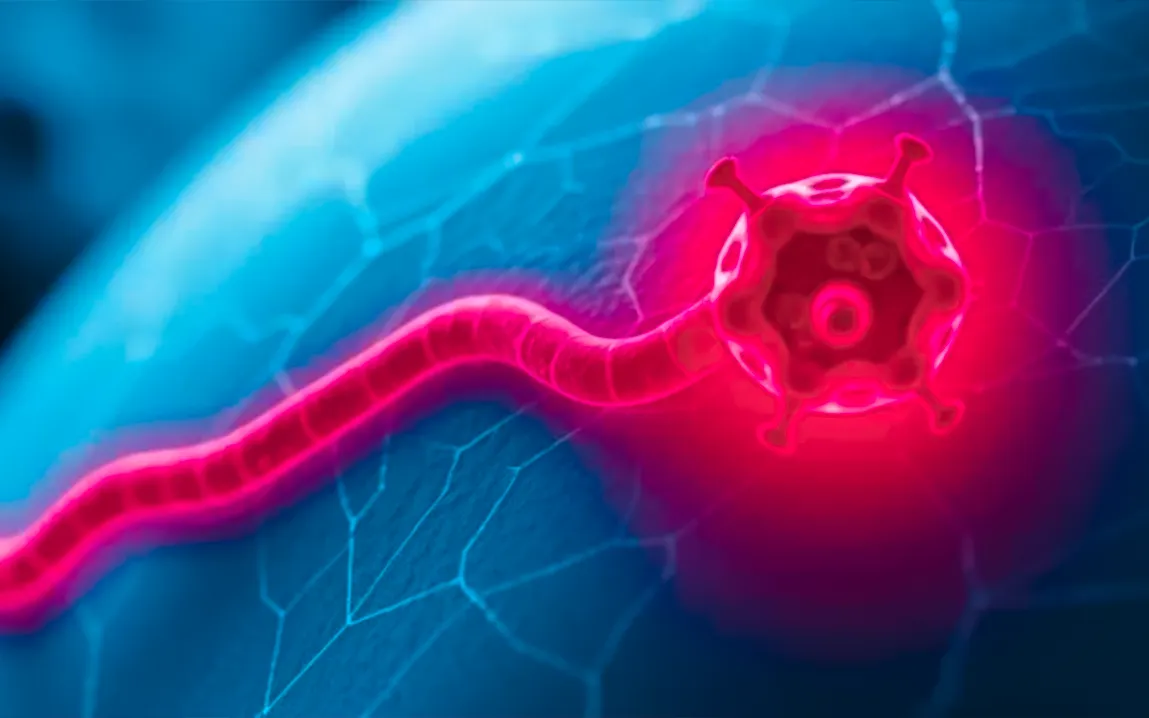

A landmark study conducted by researchers from the University of Iowa, in collaboration with Texas Biomedical Research Institute and Boston University, has shed light on how the Ebola virus, or EBOV, eventually reaches the skin surface. This study, published in the journal Nature Communications, researches the role of the skin in the virus’ transmission-a direction hardly taken by previous studies. For a long time, the attention in Ebola virus transmission has been centered around bodily fluids like blood, vomit, or saliva. However, this new study puts into light how the virus manages to penetrate and spread through the skin, something that could make great differences in infection controls and containment during outbreaks.

The Virus’s Journey to the Skin: How Ebola Causes Skin Symptoms

Ebola virus is notorious for the high fatality rate it causes and the severity of symptoms. However, most studies have focused on its entry through the mucous membranes of the eyes, nose, and mouth. On the other hand, this latest research has some evidence to show that the skin, particularly the outer layer, might also be an entry point for the virus into the body. The dermis and epidermis are the two main layers of skin in which EBOV can infect multiple cell types and reach the surface.

Ebola virus is generally spread through direct contact with body fluids from an infected individual. Infection of Ebola virus takes place through exposure to infectious material via mucous membranes, cuts, or abrasions on the skin. After entry, the virus immediately targets immune cells, including dendritic cells guarding the entry into the immune system. The dendritic cells are responsible for recognizing the pathogen and thus creating an immune response. Infection of these cells allows the virus to escape the initial defense mechanism of the body and further disseminate into the bloodstream to eventually infect other organs like the liver, lungs, and kidneys. However, the new study explores how the virus travels from the site of entry into the skin to its eventual consequences for the body, including the risk of onward transmission from infected skin.

Mechanisms of Infection in the Skin

The researchers followed the pathway of Ebola virus entry through the skin, its travel within, and its release to the surface, events that might spread the virus to another host. Using skin models, the researchers watched how the virus infects and spreads through layers of the skin. The main finding is that the virus infects not only skin immune cells but also the basal cells of the bottom layer of the epidermis.

What makes these findings especially important is that these infected skin cells, which can be present without symptoms showing on the skin’s surface, actually can harbor the virus. In other words, one could have viral particles on the skin surface and not appear ill or with typical signs of Ebola infection. While the skin may seem to be an outer barrier, the virus can still find a way to penetrate deeper layers of the dermis and epidermis. The results of this study indicate that even intact skin—without visible cuts or abrasions—can be an entry point for the virus under the right conditions, such as in cases of long exposure to infected bodily fluids or contaminated surfaces.

The Role of Skin in Ebola Virus Transmission

This was quite a profound finding as it described how Ebola got transmitted from one individual to another, especially in healthcare settings and during outbreaks. Healthcare workers are highly vulnerable due to their contact sometime directly with bodily fluids of infected patients. Gloves, gowns, and face shields cannot block the virus from reaching the exposed skin through breaches in personal protective equipment or by accidentally touching contaminated surfaces. This study gives more evidence that skin can be a more significant route of transmission than previously thought, especially when it is in contact with infected persons’ body fluids.

The new information could even affect the general public’s perception concerning the spread of the virus in addition to the health care workers. Close contact with an infected person can rapidly transfer the virus onto skin through shaking hands, a touch, and even by inadvertently touching infected objects. What this research outlines is the subtlety of Ebola transmission through skin-to-skin contact may not be readily apparent. This challenges the assumption that only visible body fluids lead to infection and suggests skin-to-skin transmission during outbreaks might be more common than realized.

Implications for Prevention and Containment

Understanding the virus’s pathway to the skin surface could also impact how future outbreaks of Ebola are controlled. The fact that the virus could reach and infect skin cells, therefore, gives protective protocols a fresh relevance, especially in high-risk environments. These findings emphasize that proper protection with PPE over the skin must be performed, including those sites which are thought of as minimally exposed. It is no longer enough to just target saliva, sweat, and blood; skin could very well be the virus vector.

Among its most central recommendations are better coverage of health care workers to ensure there is no skin showing anywhere. This would improve gloves, gowns, and face shields so the skin couldn’t touch a virus in any manner whatsoever. Researchers also recommend testing more effective disinfectants or antiviral agents that can be used on the skin to prevent contamination. Increased training and awareness among health workers and the public in the role of the skin in Ebola transmission enables better decision-making in the face of outbreaks.

This might also spur the development of vaccines or treatments that could not only prevent the internal spread of the virus but also block infection on the skin’s surface. A new line of defense against Ebola, applied externally, might be possible by targeting those specific skin cells that permit entry of the virus.

Research into how the Ebola virus traces its route to the skin surface is one of the important leaps in understanding how this virus causes an outbreak. It signals that skin, though it may be an external barrier, is not impervious to infection. The implication is really broad and might change drastically how health systems cope with outbreaks. This new knowledge can also be used to develop improved protocols for preventing transmission and better protection measures for healthcare workers and the general public. With this recognition of the skin’s role in Ebola pathogenesis, researchers and policymakers can go a step further in controlling future outbreaks and saving lives. With Ebola still being among the global health concerns, such findings are likely to be in the limelight, shaping the next generation of response strategies.