Pregnancy is often characterized as a metamorphic and magical journey for countless parents, yet it is also an inherent period of immense change, both physically and emotionally. The other major factors influencing a baby’s development include stress during early pregnancy; this is emerging as an important area of concern for scientists and health professionals. To this tough and somewhat inattentive view of a woman being a living vessel for a child to grow inside, recent research has illuminated how very early exposure to stress during gestation has long-established lasting effects on the physical, emotional, and cognitive well-being of children and their continuum into adulthood.

The Critical Window of Early Pregnancy

Early pregnancy, or the first trimester, is a very sensitive period in the development of the fetus.

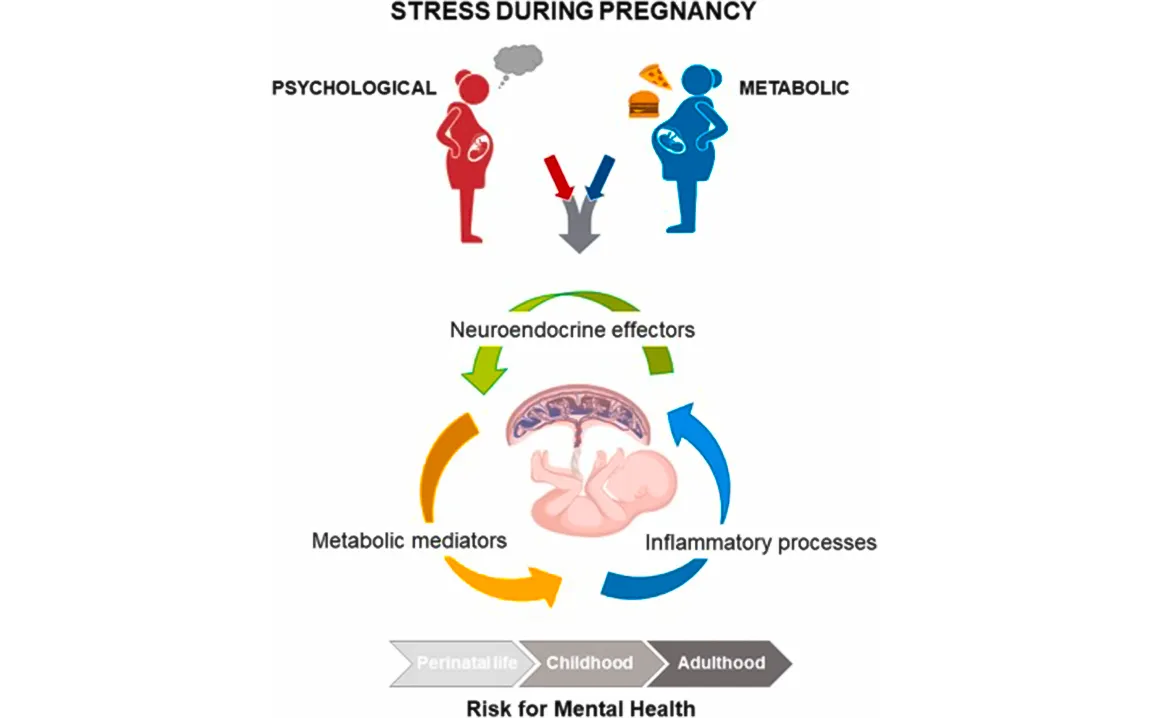

At this stage, the major systems of the baby’s body, such as the brain, nervous system, and organs, begin to form. External factors such as maternal stress can considerably influence these processes. If a pregnant person experiences stress, her body secretes stress hormones like cortisol. Small bursts of cortisol are a part of the natural response of the body to challenge, but prolonged exposure disrupts fetal development. The placenta, the lifeline between mother and child, is not impervious to the stress hormones of the mother. Studies have shown that high levels of maternal stress alter the placental barrier and enable the stress-related chemicals to reach the developing fetus. Early exposure to such elements has been associated with changes in brain structure, immune function, and even gene expression in the child.

How Stress Affects the Developing Brain

Stress during the early weeks of pregnancy can set up lifelong markers in the brain. Maternal chronic stress is observed to influence the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis development, which regulates the body’s response to stress. A disordered HPA axis in the fetus may make one more sensitive to stress throughout life and less able to cope with difficult situations as they grow older.

Additionally, the prefrontal cortex, responsible for decision-making, impulse control, and emotional regulation, may be further compromised. This enhances the risk for mental health disorders such as anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the offspring.

Physical Health Consequences

The impact of stress during early pregnancy is not limited to mental health. Physical health consequences on the offspring are also possible. Evidence has accumulated indicating that prenatal stress increases the risk for cardiovascular problems, metabolic disorders, and immune system dysfunction. For example, children whose mothers had high levels of stress during pregnancy might have a higher risk of developing high blood pressure or type 2 diabetes later in life.

One reason for these outcomes is that maternal stress can impact fetal growth and development by impeding blood flow or altering nutrient delivery through the placenta. An infant can then be of low birth weight or born prematurely, conditions that set up a lifetime of health difficulties.

Emotional and Behavioral Effects

Children of parents experiencing high levels of stress during early pregnancy are also at increased risk for disturbances in emotional regulation and behavior. Prenatal stress has been associated with increased aggression, mood dysregulation, and difficulties in healthy interpersonal relationships. These may emanate from differences in connectivity within the brain and alterations in stress regulatory mechanisms that make adaptation to emotional and social challenges poor.

Interestingly, these effects are not hardwired by the biological process. The postnatal environment determines crucially the child’s outcomes. Supportive, nurturing caregiving can mollify some of the negative impacts of prenatal stress, emphasizing the importance of a loving and stable environment after birth.

Intergenerational Effects

One of the more alarming aspects of prenatal stress is that it has the potential to influence not just the exposed individual but also future generations.

Epigenetic studies have demonstrated that stress can affect gene expression in ways that are transgenerationally heritable. In this fashion, the stress of a grandmother during pregnancy can affect the life course of a grandchild. These findings provide a biological basis for the long-term effects of early pregnancy stressors, which is a public health concern.

Breaking the Cycle: What Can Be Done?

Fortunately, interventions and changes in lifestyle can go a long way in mitigating the impact of stress during pregnancy. Health professionals encourage expectant parents to invest energy in their self-care by engaging in regular exercise, proper nutrition, and sufficient sleep. Foundational habits, like these, serve to regulate cortisol levels and contribute to overall wellness.

Such support is equally important in relation to mental health. Counseling, mindfulness practices, and stress management techniques will help reduce the psychological impact of pregnancy-related or external stressors. It also constitutes added value in social support from the partner, family, and friends, which is important to create a positive atmosphere for the parent and baby.

At the same time, even healthcare systems are able to work as mitigants. Ensuring a network of support for expecting parents through prenatal education, routine care, and mental health services creates an avenue through which expectant parents feel cared for throughout their pregnancies.

Awareness and Social Change

However, while individual effort is important, systemic change is what will fully bring about change in prenatal stress. Many of these stressors, such as financial insecurity, lack of healthcare access, and societal pressure, are systemic in nature. Policymakers can make a difference by investing in programs supporting families: paid parental leave, affordable childcare, and universal access to healthcare.

Greater awareness of the importance of mental health in pregnancy can reduce stigma and help more parents seek the help they need. It will take a culture that supports pregnant individuals and their families through community-based initiatives, workplace policies, and public health campaigns.

A Brighter Future for the Next Generation

What a sobering truth-that early pregnancy stress can shape a child’s future-informs how much more connected we are to one another than we might have ever imagined. It also speaks to the resilience of human development: with good systems of support around them, the negative influences of prenatal stress can be minimal, and the children can thrive despite challenges.

Every action we can take in support of parents-to-be-each personally, communally, or structurally-is significant insurance for the optimum, healthy life of the generations to come. The wiser this science of prenatal stress informs us, the more we know one thing above all else: the nurturing of mothers is an investment in long-term health and well-being in children.