In the fall of 2021, archaeologists from the Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo, made a sensational discovery near Tyrifjorden, west of Oslo, Norway. Excavation of the ancient grave field revealed a small reddish-brown sandstone block, about 31 by 32 centimeters in size. Dubbed since the Svingerud stone, this plain stone is now considered the world’s oldest known rune stone, inscribed at about 1,800 to 2,000 years ago or from the early Roman Iron Age.

This is a find of inestimable importance: runes are the letters of the ancient alphabets used by Germanic peoples, and the inscriptions on the Svingerud Stone represent a very rare glimpse into the early use of written language in Northern Europe. While the oldest known runic inscriptions were usually restricted to smaller objects, like combs and amulets, never before has a rune stone of this age been found.

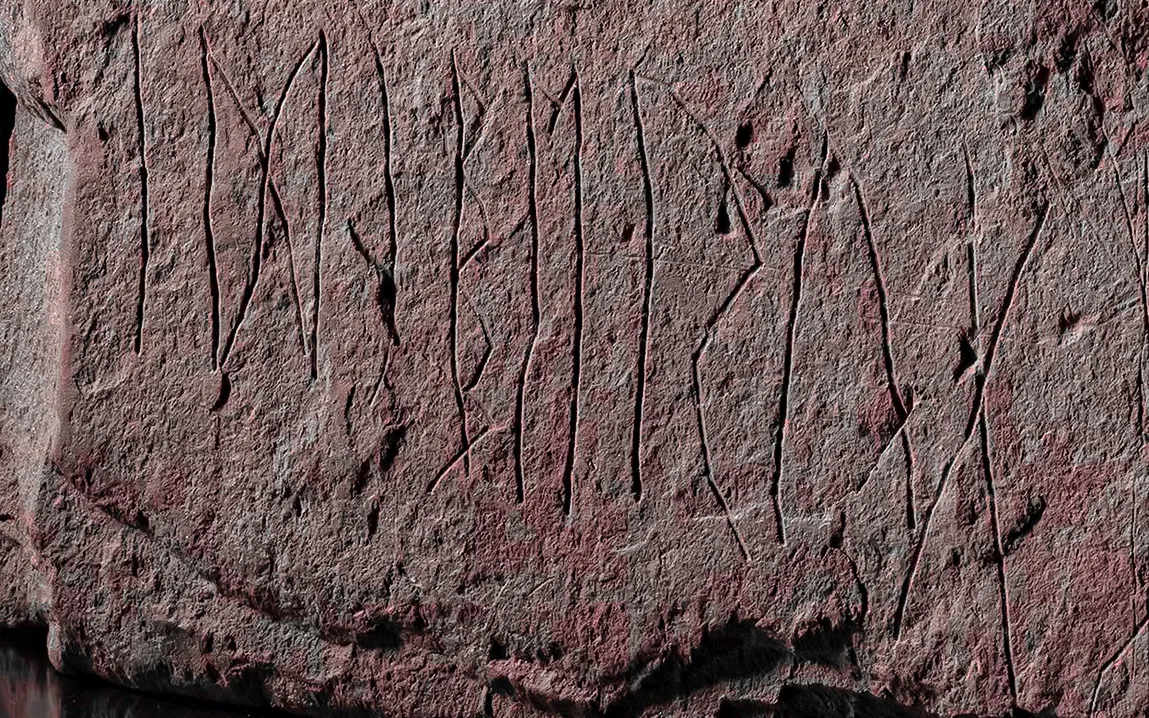

The inscriptions on the stone are done in the Elder Futhark, the oldest form of the runic alphabets. Perhaps the most interesting feature about the Svingerud Stone is that it bears the first three runes of this alphabet: ᚠ (f), ᚢ (u), and ᚦ (th). This combination represents the earliest known use of these runes consecutively and therefore offers insight into the development of written language at that time.

The stone inscriptions proved to be complex to decipher. Part of it contains eight runes that transliterate to “idiberug” or “idiberun.” There have been a few meanings put forth by scholars for this combination. It could be a woman’s name, Idibera, and thus be an inscription that says “For Idibera.” Still, the possibility remains that it is a surname, as in Idiberung. Indeed, the meaning is still under research, exemplifying the problems normally associated with translating old scripts.

The implications of the Svingerud Stone are huge, thus setting new views on early literacy and language in Scandinavia. It indicates that the use of runes was both more extensive and at an earlier stage of development than previously thought. This forces revisions in current theories about the timeline for written language in the region and opens new avenues for research into the social and cultural contexts in which these inscriptions were created.

That further contextualizes the setting of this stone within a grave field. That makes one question about the relationship between the runic inscription and burials during the Roman Iron Age. Were these inscriptions to honor somebody, to mark territory, or to form part of some ritual? An answer to any such queries would most likely specify what early Scandinavian societies believed and what their practices were.

Today, the Svingerud Stone is housed at the Museum of Cultural History in Oslo, where intensive study of it continues unabated. Advanced imaging techniques and comparative analyses go into action to glean more from the inscriptions. Every new discovery contributes to the nuanced view about the early use of runes and the societies that produced them.

This is the incredible discovery that has caught the attention of archaeologists, linguists, and historians from every part of the world. It is a reminder of how much of human history lies buried under the dust and how ancient relics can reveal a continuous mystery. As research unfolds, the Svingerud Stone will no doubt add to our insights into early written communication and the cultural dynamics of ancient Scandinavia.

The Svingerud Stone is a milestone in the study not only of runic inscriptions but also of early literacy in Northern Europe. It pushes back the timeline for written language in the region and provides a tangible connection to the people who inhabited Scandinavia almost two millennia ago. As scholars continue to piece together the puzzle of this ancient artifact, we can look forward with anticipation to new insights into the dawn of written communication and the complex societies which gave rise to these early scripts.